We are Hiring! Click here to see our open positions.

Learning From an Old Fashioned “Run on the Bank”

calendar_today April 5, 2023

By Frank A. Burke, CFA, CAIA, Chief Investment Officer, PPB Capital Partners

and

Anton W. Golding, Associate, Fund Manager Analyst, PPB Capital Partners

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

— George Santayana

Déjà vu

Let’s set the stage for a dramatic, volatile and fascinating turn of events in American banking history…

- Executives at a mid- to large-sized bank made risky bets with balance sheet capital as they attempted to drive profits.

- Bets made with little regard for the potential costs of negative movements are, by definition, “risky.” To fan the fire, the nature of the bank’s business model made it highly susceptible to customers withdrawing large deposits quickly.

- When the risky bets lost value, the bank’s solvency came into question. Depositors and institutional peers lost faith, which sparked an historic bank run.

- Such panic created a contagion across the banking sector, requiring J.P. Morgan to step in and provide support to buoy the American financial system.

If you think the recent story of Silicon Valley Bank checks all these boxes, you’re not wrong. Strangely enough though, this is the script that played out as Knickerbocker Trust experienced its own “run on the bank” 116 years ago. It initiated the Panic of 1907, one of the most severe market contractions of the 20th century.1

Not surprising, market regulation at the turn of the 20th century was lax compared to today’s standards. Widespread stock and market manipulation was rampant and unchecked, leading to massive price bubbles and market-wide volatility. Despite a new regime of government oversight as a result of President Theodore Roosevelt’s economic crusades, high finance was still very much like the wild west.

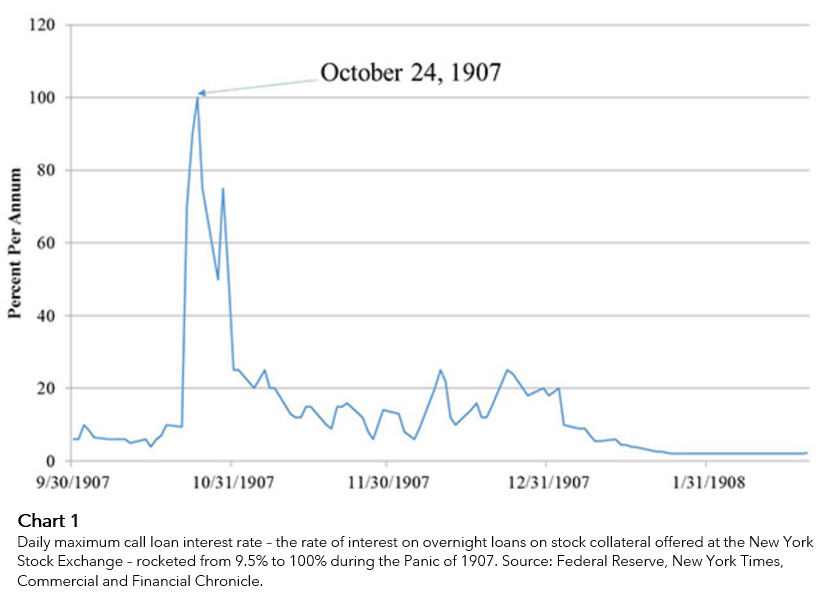

In October 1907, speculators Augustus Heinze and Charles Morse and associated banks suffered significant losses after a failed attempt to corner the stock of United Copper. To quell any bank runs and calm depositors, The New York Clearing House offered loans and clearing house loan certificates to these banks.

Several days after, however, it was discovered that a relatively large bank and Wall Street institution, Knickerbocker Trust, and its president, Charles Barney, had also been involved in the cornering of United Copper. Upon hearing this, customers rushed to pull their deposits from Knickerbocker. After several failed attempts to shore up liquidity and after nearly $8 million gone out the door, Knickerbocker suspended operations, igniting a financial crisis.1

J. Pierpont Morgan famously led a consortium of Wall Street’s largest financiers to aid struggling banks and to keep the New York Stock Exchange open. For acts like this, Mr. Morgan was often considered the U.S. Central Bank prior the formation of the Federal Reserve. Affairs like the Panic of 1907 led to mass dissatisfaction and shined a spotlight on the lack of actual regulation and government oversight. But after more than 100 years and thousands upon thousands of pages of reform and regulation, some banks still find creative ways to “do dumb things.”

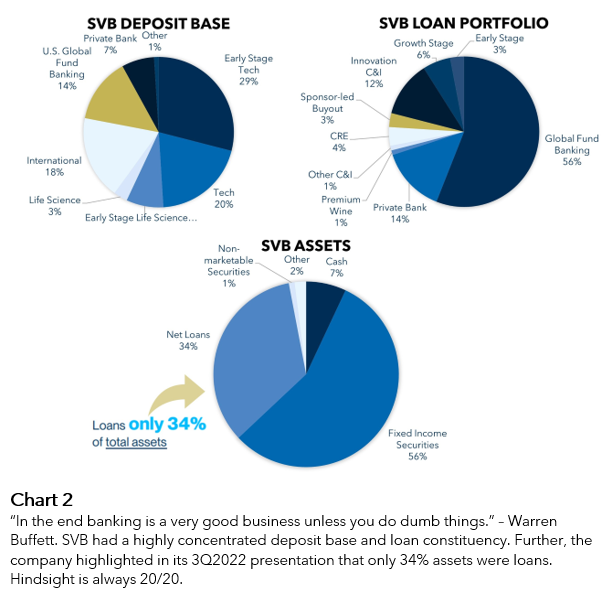

While not alone in its actions, Silicon Valley Bank’s poor risk management decisions and unique client concentration resulted in events that were eerily similar to Knickerbocker Trust in 1907. The most remarkable coincidence is the return of Mr. Morgan’s legacy company to backstop institutions—like First Republic Bank—and reestablish the American public’s confidence. To paraphrase Mark Twain … Sometimes, history truly does rhyme.

Blood in the Streets

Historically, some of the greatest investments have been made amid crises. It is never an easy decision to move against the crowd and invest when there’s blood in the streets, but it can be a defining moment for many fund managers.

Looking to a more recent financial market panic, several market participants won big in the wake of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) by buying assets at incredibly distressed prices. Some hedge funds did remarkably well in that environment, particularly by investing in banks that were hit hard by the crisis. After his famous big short of the U.S. housing market, John Paulson bet on an economic and market recovery and deployed capital into stocks like Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and Citigroup, all of which had been deeply impacted by the fallout.

Just a few blocks away in Manhattan, Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square took a substantial stake in Wachovia Corp as a bidding war for its banking business began between Citigroup and Wells Fargo. Pershing Square identified the company’s other businesses, including its wealth management arm, as overlooked, quality assets at highly distressed prices. After the initial bid, the fund continued to build a significant position until Wachovia merged with Wells in its entirety.

While being greedy when others are fearful is easier said than done, Paulson and Ackman were not alone, as Berkshire Hathaway and Oaktree poured billions of dollars into beaten down assets throughout the GFC. Allocating to managers who have proven to be agile and opportunistic is vital for outperformance in uncertain market environments.

There are many parallel opportunities today with Silicon Valley Bank, as a consortium of debt holders lobby for a sale of the holding company’s non-bank assets, including the wealth management business, SVB Private. Further, large alternative asset managers like Apollo and Blackstone2 have been evaluating the now defunct bank’s loan books to find potential dollars they can buy for pennies.

Some have predicted that the recent bank failures are simply the start of something much bigger, citing a broadening weakness across capital markets. According to Bloomberg, corporate debt in distress increased by $69 billion, reaching $624 billion, in just the last few weeks.3 This may create significant opportunities for distressed credit investors to deploy capital, particularly those in lower and middle markets. While growth investors had a significant advantage in the declining rate environment of the past fifteen years, the current regime and tightening credit markets may signal the beginning a deep value bull run.

Though the ongoing upheaval of regional banks is currently a much more contained event than the Great Financial Crisis, it’s natural to wonder who the winners will be this time.

Footnotes and Important Disclosures

1 https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/panic-of-1907

2 https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/apollo-blackstone-eye-svb-assets-bloomberg-news-2023-03-14/

3 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2023-03-28/svb-credit-suisse-crises-trigger-distressed-debt-increase

This report is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer to sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy, any interest or investment in the Fund. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

This document or any part thereof may not be reproduced, distributed or in any way represented without the express written consent of PPB Capital Partners, LLC. A copy of PPB Capital Partners, LLC’s written disclosure statement as set forth on Form ADV is available upon request. Although the information provided has been obtained from sources which PPB Capital Partners, LLC believes to be reliable, it does not guarantee the accuracy of such information and such information may be incomplete or condensed. PPB Advisors, LLC is an affiliate of PPB Capital Partners, LLC by virtue of common control or ownership.

The statements included in this material may constitute “forward-looking statements” and are subject to a number of significant risks and uncertainties. Some of these forward-looking statements can be identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “believes”, “expects”, “may”, “will”, “should”, “seeks”, “approximately”, “intends”, “plans”, “estimates”, or “anticipates”, or the negative thereof or other variations thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology. Due to these various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results of the actual performance of an investment may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements and no assurances can be given with respect thereto.

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- January 2019

- June 2018

- December 2017

- June 2017

- March 2017

Recent Posts

- Investment check-in: why now may be an opportune time to diversify with alternatives

- Is now the right time to outsource the operations of your in-house alternative investment funds?

- Financial Advisor Magazine: The Hunt for Alpha

- Across the Pond

- 2024 Global Outlook

- With Intelligence: PPB Capital Partners seeking specialty finance strats

- With Intelligence: PPB Capital Mulls Sports Financing Opportunities

- PPB Capital Partners Promotes Amanda Bannon to Chief Operating Officer

- Time to Buyout?

- PPB Capital Partners Named One of Philadelphia’s Fastest Growing Businesses

- Financing the Future

- Getting to know Carly Kramer of PPB Capital Partners

- Getting to Know Matt Williams of PPB Capital Partners

- Judge for Yourself

- Getting to Know Anton Golding of PPB Capital Partners

- PPB Capital Partners Expands Distribution, Operations Teams To Serve Wealth Advisor Partners, Meet Growing Demand

- Office Space Oddity

- Maintaining Face Time in a Remote World

- Getting to Know Andrew Sussingham of PPB Capital Partners

- Creating Custom Solutions

- Break on Through (to the Other Side): Post-Pandemic Trends and Opportunities in the Hospitality Industry

- Getting to Know Ed Chandler of PPB Capital Partners

- Learning From an Old Fashioned “Run on the Bank”

- Connecting a Remote Staff Through Culture

- Aligned with Wealth Advisors

- “There’s No Place Like Home…”

- Get to Know Vikki McLaughlin of PPB Capital Partners

- Loyalty

- “It was the Best of Markets . . .”